THIS IS AN UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT

Hello, I'm John Milewski. Welcome to Wilson's Center NOW, a production of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Today, we take our quarterly look at the latest edition of the Wilson Quarterly. And as always, I'm joined by the editor of the publication, Stephanie Bowen. Stephanie, welcome. Thanks for joining us. Thanks for having me. The current issue is titled In Search of Our Narratives, and the subtitle says Notable public and private sector leaders share their thoughts on how to achieve a brighter global future.

And one of those contributors, Robert Daly, director of the Wilson Center's Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, also joins us for the discussion. Robert, hello to you as well. Good to be with you. So, Stephanie, let's begin as we do traditionally and have you tell us about the issue. Give us an overview. Sure. Well, the winter issue, we knew it would be coming out of after a year of historic elections, during a time when there was a great transition both in the United States and elsewhere.

And we really wanted to have an aspirational look at broad themes in foreign policy. So, you know, we know the world is a little bit mired in disinformation and partizan politics, and we wanted to offer something different, something that could help guide us during times of transition. And what we ended up with was a pretty incredible roster of, as the subtitle says, notable public and private sector leaders sharing the narratives that have really helped shaped their views on the world and things that have ideas that have guided them and the world through pastimes of challenge.

So, you know, Stephanie, I'm a huge fan of the publication and your work, but I really have to say you outdid yourself this time. This is really a stellar issue. And Robert, I'll tell you that Robert's piece is titled One Mountain to Tigers. Neither China nor the U.S. will fall. Can They Learn to Coexist is the teaser on that article.

And Robert. Stephanie, the way this works behind the scenes here is when a new issue is ready to come out, Stephanie and I discuss well, when we do a now episode, which author will we invite to join us? Every time we had that discussion before we made our call, Stephanie would begin by saying, Well, Robert Daley's piece is really excellent.

And so it just kept coming up time and again. So you were the choice, sir. And tell us, sum up the competing narratives. Let's start there. Since this is an issue about narratives, what are the competing, the U.S. narrative and the China narratives? Well, this was really two different American narratives about China. China has them about the United States in a slightly different way.

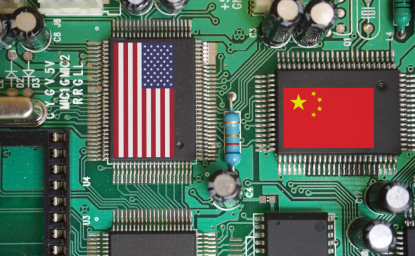

And the idea behind the piece is that both Beijing and Washington are not entirely sure whether they want to look at this relationship through a primarily political geopolitical lens, competing in security or through an economic lens. And they tend to waver back and forth between the two. If you only consider the political interests of each side as they define them and not yet critiquing whether they're right or wrong about their security interests, but as they're broadly defined, then you end up thinking, we're headed for a bifurcated world with both sides wanting different things for their own nations for the global order, such as it is both countries wanting to be the tiger on the Hill,

wanting to be the primary nation shaping global order. Two very proud nations, nations that are unwilling to compromise and that are currently building up blocs or allies for competition with each other. It looks like a bifurcated world based on our sense of risk or perception of risk. At the same time, as everyone knows, we remain economically deeply intertwined, despite the fact that both sides have been carrying out selective decoupling for a while.

Both sides want to be less vulnerable to each other. But the fact is that through a purely economic lens or economic narrative, they remain fairly complementary and deeply integrated, even after the trade war that began in the first Trump administration. And that was deepened in many senses by the Biden administration. We continue to trade with and depend on each other and the corporations, the markets who want to insist on economic prerogatives, economic narratives want to wish away all these security concerns as unnecessary, as paranoid, as whatever is, whatever it is, and to insist on the economic market prerogatives.

And there's a struggle overall. Over the past several years, security has been gaining an upper hand, But we're not willing to let go of the economic because while we are worried about each other, we are wargaming each other. We are building up capabilities and blocs against today where there might be conflict. In fact, conflict doesn't seem to be right around the corner.

So we're still holding on to the economic. And so that was what most of the piece was about, was looking at that dichotomy and how it might play out. A longstanding narrative about China that China has used Chinese leadership is using that too much freedom is a bad thing. It leads to chaos and that too much individualism is another bad thing, that it leads to an unwieldy, essentially society that does not work.

Conventional wisdom has said that in the era of global communication, instantaneous global communication and social media and all these things, that those types of notions would begin to break down and people would yearn for freedom the way Americans define freedom. You just came back from another of your trips to China. What can you tell us about that narrative and whether it is losing any momentum or whether it's still strong among the Chinese populace?

Well, this is this is complicated and it's an ancient problem in China, Of course, the way that you just correctly outlined it. Too much freedom is a bad thing. The key question becomes who gets to say how much is too much? Right? And the Chinese answer is a benevolent but all powerful government that you can count on you, the people of China, to wield its power in your interests because it's benevolent and because China's economic success of the past 50 years proves that it has the right formula.

But right now, China's economy is not doing well. They're in the midst of their biggest economic crisis since the reform opening period began. And the Chinese people are, I would say, down at mouth. They are pessimistic. They are grumbling about their government. But it's more in sorrow than anger. It's nothing like the seeds of revolution. They are going to wait it out because as I said in the article, while they're deeply dissatisfied with the current situation in China, they see and this is tenuous, it's an anecdotal claim in the absence of polling, in the absence of voting, they seem to buy the government's claim that it's either continued development.

Even if that's slowing, that can only be provided by the stability which a strong state I gives to China. Or, you know, it's a binary choice, some form of what the Chinese call chaos or not. When you ask them exactly what that looks like, you never get a clear answer. If there's no Communist Party. Does the province of Hubei invade the province of Hunan?

It's not clear. But there's a strong sense, I think, even among the Chinese people, that in fact, they do face a binary choice because China was so poor and so put upon for so long until so recently, a society with a living memory of mass starvation, something that Americans have a hard time appreciating, that they tend to place their bets on the side of stability, even if that means they have to put up with a more repressive government than they would like.

I think that many of the Chinese people still up for stability, and of course, they do that in part because of the Communist Party, through its Ministry of Propaganda and through other devices, keeps their threat perceptions high, tells them that they face a West, a United States, which is determined to destroy them, and therefore a little privation isn't such a bad thing.

And again, my sense having just been there, is that while the people are more unhappy with their government than they've been probably since 1979, they are going to do what the Chinese call eat bitterness and put up with it. So, Robert, we do a little tag team here, so I'm going to hand it off to Stephanie now and she'll have a few questions for you.

Thanks. You know, one of the things that I always love about your pieces, Robert, and your analysis of the China-U.S. relationship is the cultural aspects of it. And you mention in your piece that the Chinese and Americans really like each other and they value each other, and they have certain things that they admire about each other. And how does that play into this competition that is heating up between the U.S. and China?

Well, this is this is in play and it's it's shifted some in both countries, you know, from the early seventies until 2016, 2018, we had what we now call the period of engagement in which individuals, institutions like universities, NGOs, corporations, absolutely. In both countries were deeply involved with each other in a way that worked for people in both countries.

It was transformative, especially on the Chinese side, because they started from a much lower level. But it also meant a great deal to the Americans who were involved in that. And as I said in the piece, we get along our sense as a family of friendship, our senses of humor are pretty compatible overall. There's an awful lot of of mutual admiration of each of each other's cultures.

America mostly admires China's traditional culture, not so much contemporary culture, but real fellow feeling and real regard. So at the beginning of the more contentious period, there was a lot of money in the bank on both sides. Now we spend some of that out. Public opinion polling in both countries now shows well over 80% negative feelings about the other country.

And that's real. And it's it's palpable in some ways. But it's the goodwill, in my own opinion, in both countries hasn't disappeared. You know, we had this very, very high regard and now a whole bunch of concerns through the trade, war and security, which have built up a lot of negative views, too. But the good stuff is still there.

And I think that our leaders could draw on it a little more. They could certainly cherish it and, you know, turn up the flame under it by increasing, you know, educational exchanges. It would be a good thing if we had more tourists going in both directions. That has stopped not because the government, the American government has said, no.

I think Americans just have the idea that China's unsafe. So I would like to see more of that people to people interaction, but it doesn't seem to be happening organically. The negative narratives go deep despite the positive ones, and this is one of the most discouraging aspects of the US-China rivalry. You know, we tend to speak in American and China.

These are political issues. I see most of these issues, even our own domestic political crisis is ultimately reflecting a cultural crisis. I think that's true in US-China relations, too. But we don't in neither country do we have a very good vocabulary for talking about that. Maybe this could be the subject of a future. Wilson Quarterly What is what is the relationship between cultural factors and what we call political factors?

We're we speak about that badly. We have international relations theorists. We don't have, you know, cultural critics who are giving us a vocabulary that is useful in this context. I find myself struggling with that a lot as I write, as I speak at the Wilson Center, because it's a vocabulary problem. Stephanie, roll with it. Go ahead. Yeah, sure, sure.

You know, it's is interesting to me, too, that, you know, you talk about how there's a we're kind of in a holding pattern, you know, and this holding pattern could last for decades.

But it also could not. So what are what are the things that we should be looking out for, as you know? Well, you know, I'm asking myself this question, too, You know, with with the political shift here in the United States and with only having a week of the new administration under our belt, it is a time to ask yourself what your assumptions, what people I guess I'll say your priors.

This is the fashionable term. I'll stick. I guess I'll stick with assumptions. What have your assumptions been? My assumption has been that because there are genuine reasons for deep rivalry and concern in US-China relations, but no factors yet that actually push us toward war. My assumption has been that we're going to be in something like a new kind of Cold War situation for several decades.

And John and I have spoken about this a lot over the past few years on this program. And my further assumption has been at the center of this dispute or rivalry between us and China would be what we call the World order peace. You know, which country is going to play the larger role in determining what kinds of global systems we have and the values that underlie the you know, I'm not sure we're still I'm not sure we're still interested in that.

Are we still interest dedicated to the global order peace or are we pursuing now a hemispheric agenda, an agenda that is more concerned with bilateral relations as measured by trade or other things? And are we less interested now in the global order peace, which is in part normative, right? Who's going to pay to uphold this order? I had thought that was going to be the center of this.

I'm not sure that is still the right question. So I'm rethinking you know, Stephanie's question raises this notion of chronic conditions don't change until they're pushed to an acute stage. And I guess that's the question out there, Robert, is do you see anything on the horizon that would be the hot point, the potential fever breaker? Well, so what are the what are the pieces of good news?

There are few and far between, but this is a big piece of good news is that neither Beijing nor Washington wants war. Both sides, while they're preparing for it, they're building their capabilities, are building their alliances. I'm convinced that the neither wants it. They are determined to avoid it if they can. And I think they can. It's going to be a long ride, a very difficult, dangerous, expensive ride.

Again, a new Cold War. But I think that that commitment is real. And neither country this is something I think a lot of people in Washington get get wrong. Neither country really wishes to harm the other. In the first instance, both countries see themselves as defending their own prerogatives and thus encountering the other as obstacles along the way.

So you'll hear people in Washington and in Beijing say things like the other is an existential threat. China wants to destroy us. China sees us as an enemy to be harmed. China sees this as an obstacle to be overcome. And that creates enough problems for us that many of these threats are real. But that's very different than a situation one in which one country wants to harm or destroy the other in the first instance as their primary goal.

That's not quite where we are, which is why I think that with wisdom and patience and yes, risk taking and expense, that we can keep it cold. And I think that that's what China hopes to do as well. You write in the piece in order to maximize their scope for action, both powers want the global system to resemble their domestic governing philosophy as closely as possible.

Who's winning in that regard? Very hard to say. China is certainly making some gains, especially in what nobody is comfortable calling the Global South. But in working with other countries that don't want their choices shaped by us, you know, Russia, obviously Iran, North Korea, certain countries in South America. But even beyond that, a number of countries that are very, very happy to have rich trading relationships with China and therefore sometimes vote with China in the UN, they sometimes seem to be drifting toward China.

On the other hand, if you look at their aspirations for their institutions and for their families, they drift more toward the West. So they don't want to make choices. They want to hedge and balance, play the two powers off against each other. That's probably their best strategy and our best strategy is probably to let them do that and not try to force it one way or the other.

So this is going to be a long, frustrating process. It would only, you know, only a radical change, a form of governmental collapse in either country could change that. And so I think that this, as I say in the piece, is going to be with us for a very long time. Another two sentences in the piece that sum up to the narratives, the U.S. has never faced a peer competitor.

China has never been a superpower in the modern sense. I mean, in many ways there's the big story, right? And in some cases you can compete your way through this, or in other cases maybe you help each other through this. Is there anything that you could even point to historically that provides a roadmap or a precedent for the two nations at this juncture?

Well, you know, Graham Allison wrote a very famous book about this called Destined for War, in which he outlined what he called the Facilities Trap. And he looks at a series of past eras in which you had a resident power, a status quo power and a rising power. And most of those situations ended in war because the status quo power felt threatened by the rise.

But this was all before the era of nuclear weapons. This was in an era of much more limited warfare. The U.S. and China have nuclear weapons. Well, we don't understand all of the escalation ladders. We do know that any conflict could go nuclear and could be World War three. And again, both sides are thinking more seriously about this.

China isn't thinking seriously enough that it will start strategic stability talks with us, which is where I end the piece with a hope that that will happen. But maybe we will get there because, as I say, they're determined to prevail, as are we. Neither side is yet willing to compromise, but neither side is, as you know, so foolhardy as to begin a war with the weapons that we have in hand.

So this is somewhat new territory. It's going to be a long haul. I hope that our discussion will be informed by a real understanding of America and China and China's side and a deeper understanding of China and the United States. And I think that that will be something that can help us get this right and avoid conflict. Stephanie, I want to throw it back to you.

See if you have any other questions for Robert before I ask you a question. Well, Robert, I'm curious. You know, you talk about the things that you wish that you would like to happen that would help the relationship and global stability. What would you what kind of advice would you give to those, you know, coming in now really in charge of U.S. China policy?

And what would you suggest they do or things that they pursue, approaches they take? We seem and it's early days in a new administration and so no predictions, but you can see on the American side also a struggle between the political or the security framework that we talked about at the beginning and the economic. The president himself seems to see US-China relations primarily through an economic lens.

He thinks that China's trade surplus with the United States is indicative of a lack of fairness. And he would like to correct that trade imbalance economics. But he doesn't seem very concerned with the big geostrategic competition, what President Biden called, you know, democracy versus authoritarianism, many within his own party, although it's bipartisan, say that this is an existential threat.

This is an epochal struggle between different worldviews, different forms of politics with Taiwan as the potential hotspot. The president himself doesn't speak that way. He doesn't speak about ideology. He doesn't speak about China as a competitor across all of the domains power. And in that he seems to be somewhat at odds with his own party. We see this, for example, in his willingness to give a lifeline to tic tac, which has been one of the major focal points of Republicans and Democrats in Congress for the past two years.

So we need to get the framing right and figure out and right size the security threat from China. I think it's overstated. I don't think it's an existential threat. It's a real threat. It's a concerning threat, but probably not existential. We need to somehow find a way to meld our economic and our geostrategic concerns, right size it and then realize that this is a long term historical process.

There's no quick answer. It's not going to be solved during Trump XI Round two. We can make some incremental moves, but the real solution will involve change in both countries over the long haul and a commitment to peace, which again, the piece of good news, I think I think we do have that despite, you know, that sometimes you hear the drums of war, that kind of rhetoric in both sides.

But I think we're really aiming for a long and difficult peace here. Robert, as always, thank you. Terrific insights. And really, we learn a lot every time we speak with you And Stephanie. I set out a question for you and it's about that. The issue, you know, in addition to Robert's terrific piece, which our viewers and listeners got a quite a preview of in our discussion today, what other pieces would you give us a highlight thesis on some of the other things that are in the issue?

If you allow me, I will go through them all because this is quite a who's who list. Sure. Here's an ideas. We have Russian dissident and journalist Vladimir KARA-MURZA who reflects on Russia's history and the Russian people's desire to want democracy to offer some advice to the West. We have tech innovator who reflects on the power of technology to connect and inspire, even while it does also bring some challenges.

We have a former Israeli ambassador to the US, Michael Oren, who writes about the ability to achieve peace in the Middle East and has some he looks at of overall U.S. foreign policy to bring some specific lessons in there. We have veteran New York Times reporter David Sanger, who's also a Wilson Center fellow. He writes about the connection between a free and fair press and a thriving democracy.

In noted human rights activist Natan Sharansky talks about how embedding human rights in foreign policy can strengthen democracies and and really support freedom fighters, while also upholding universal rights and strengthen strengthen governments. Former World Bank President David Malpass lays out a vision for global prosperity that also highlights the need to address global inequality. We have a really interesting piece that I think complements a lot of what Robert talked about from former Indian Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao.

She writes about the importance of the Indo-Pacific region in the future prosperity of America. We have longtime champions both inside and outside the National Endowment for Democracy. Frank Fahrenkopf and Ken Wallach, they really they reflect on Ronald Reagan's historic Westminster speech on democracy to make the case for promoting democracy. Our very own Mark GREENE writes about an American approach to foreign assistance that's based on his his time as you as a as U.S. aid administrator.

But it starts way back for when he taught in a Kenyan village Tanzania. In businessman model, he makes the case that Africa really needs to be on everyone's radar. And he gives a lot of examples of how different governments in the world can engage with the continent. Former Colombian President Ivan Duque talks about how an approach to the Americas as a whole will not only strengthen Latin America, but also strengthen the U.S..

And Baroness Catherine Ashton talks about what it means to be European in a post-Brexit world. It's really is quite a lineup. Thank you for letting me run through it all with my notes at hand. Sure, sure. Robert, you were in great company on that table. Great company and honored to be in the magazine. And thanks to both of you and congratulations on the article and on the latest edition of the Quarterly.

We want to tell our viewers and listeners the other good news is it's absolutely free if you come to Wilson Center dot org. You can find that resource and many, many others all presented to you as a public service. We hope you enjoyed this edition of Wilson Center now and that you'll join us again soon. Until then, for all of us at the center.

I'm John Milewski. Thanks for your time and interest.